Conjugate Method, popularized by Louie Simmons, is a training systems that uses consistently varying exercises to develop, strength, power and athleticism

In conjugate system barbell training will only make up 20% of your exercise volume. While 80% will be dedicated to special exercises, accessories and increasing general physical preparedness (work capacity).

There are three methods of traing in which conjugate is structed around

Max effort (90%+) – recruits high threshold motor units, teaches lifters to grind and adapt with near maximum weights.

Dynamic effort (75-85% or 50-60% bar weight with bands or chains making up about 25% of total resistance) - Due to the high levels of acceleration, this method builds power (Power = Force x Distance ÷ Time). It forces the body to recruit high threshold motor units and develops rate of force production. Using only straight weight, even if maximum intent is used the barbell will naturally decelerate. This is due to inherent increased mechanical advantage after a sticking point is passed. To combat deceleration, accommodating resistance is used to reflectively increase force production past the sticking point up to peak contraction (fully locked out).

Repetition method – builds hypertrophy, glycolic and aerobic energy system helping increase GPP. Sets are taken to failure, only when this happens will this recruit maximum motor units.

Workout Structure

Each workout should look something similar to this

• Max effort or Dynamic effort

• Supplemental or secondary Dynamic effort

• Accessory

• Accessory

• Accessory

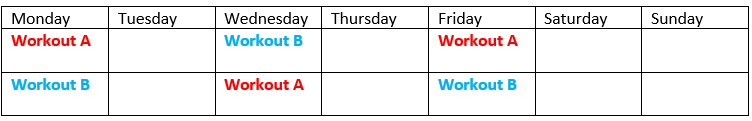

Weekly Structure

The micro cycle (weekly plan) structure should look something similar to this

Day 1 – (ME) Max effort upper

Day 2 – (ME) Max effort lower

Day 3 – (DE) Dynamic effort upper

Day 4 – (DE) Dynamic effort lower

Example Week

Here is what an example micro cycle (week) may look like…

Day 1 - Max Effort Lower

• (ME) - high bar low box squat

• Cambered bar wide stance good morning – 4x5

• Single arm dumbbell rows – 4x12

• Reverse hypers 4x20

• Standing banded crunch – 100 reps AFAP

Day 2 - Max Effort Upper

• (ME) Upper - Floor press

• Close grip Bench press with 40lb chains – 5x5

• Laying dumbbell triceps extensions – 4x12

• Dumbbell pull over – 4x12

• Front + laterals raise – 3x12

Day 3 -Dynamic Effort Lower

• (DE) Squat - 80lbchain squats 10x2 @ 55%, 60 seconds rest

• (DE) - 2” banded sumo deficit deadlifts – 10x1 @ 55%, EMOM (every minute on the minute)

• GHR – 4x10

• Chest supported row – 4x10

• Side bends -4x20

• Banded hamstring curls – 100 reps AFAP

Day 4 – Dynamic Effort Upper

• (DE) 3 grip bench press with bands 9x3 @ 55%, 30-45 seconds rest

• Dumbbell press – 5x5

• Dumbbell rollbacks – 3x12

• Seated cable rows – 4x10

• Straight arm pulldown – 4x20

• Band pull apart – 100 AFAP

*Make sure there is at least 72 hours between dynamic effort work and Max effort.

A Deeper Dive

Note: on all days use different assortments of variations, special bars, changes in stance or grip, addition of accommodating resistance or manipulating range of motion (making it a longer or shorter distance than normal).

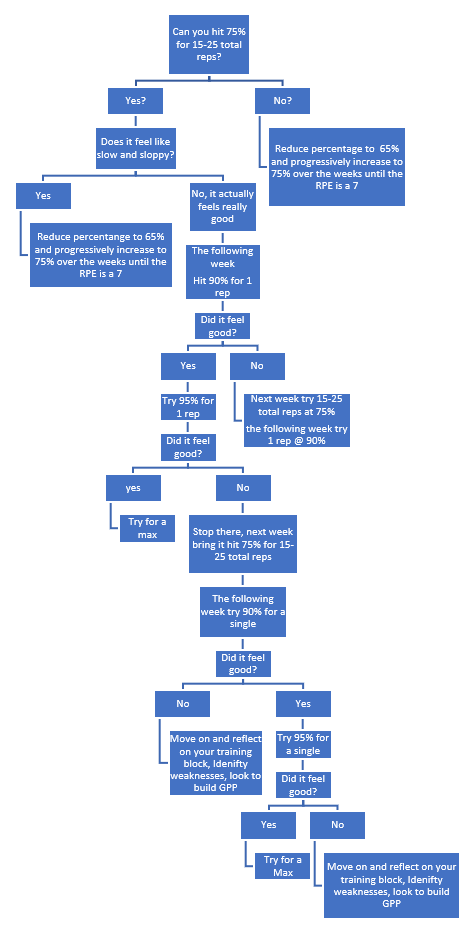

Max Effort Should be a 1-3 rep max

These should not be the primary competition lifts something that may resemble them.

Max Effort Lower example

Week 1 – High bar Narrow stance low box squat

Week 2 – Cambered bar 80lb chain squat

Week 3 – 2” deficit deadlift with 1” bands

Max Effort Upper example

Week 1 – 2 board press

Week 2 – Dead pin bench press with 100lb chains

Week 3 – Wide grip legless Buffalo Bar Bench press

Dynamic Effort should be same exercise done in 3-week waves 50-60% bar weight and with 25% accommodating resistance.

Dynamic Lower Squat Example

Wide stance 12” box squat + 80lbs in chains

Week 1 – 12x2 @50%

week 2 – 10x2 @ 55%

week 3 – 8x2 @ 60%

Dynamic Lower Deadlift Example

2” Deficit + 1” Banded Sumo deadlift

Week 1 – 12x1 @50%

week 2 – 10x1 @ 55%

week 3 – 8x1 @ 60%

Dynamic Upper Bench Example

Swiss Bar 40lb Chain Floor press

Week 1 – 9x3 @50%

week 2 – 9x3 @ 55%

week 3 – 9x3 @ 60%

Supplement lifts

These lifts should be lifts a weak area. For squat and deadlifts good mornings are a good place to start and for Bench close grip bench press is a good starting point. Usually done for sets of 3-6 reps.

Accessories

These are specific muscle groups that need strengthening. Squat and deadlift that is hips, glutes, low back, hamstrings, upper back, core. For the Bench is triceps, lats, upper back and shoulders. These accessories should be taken to failure on most accounts.

80% of Your Training Volume

The bulk of the training program comes from everything that is not the main lift. Being smart about where you are putting your energy will produce long term results. The base of performance is development a larger work capacity thought increasing GPP. That is done over years not weeks. Focusing on “smaller” exercises come at a much lower recovery cost meaning you can and should push the accessories hard. Because they are far less demanding on the nervous system, they need to be train to failure to reap the benefits.

In addition to increase GPP because you are rotating through different exercises on an annual time scale you place the body in slightly different positions. You are forced to apply maximum effort to overcome the slightly different variances in torso, limb and joint angles. Taking a conjugate approach over time will help prevent over use injury, makes you more robust, makes you more adaptable to changes in the environment and allow you to break through plateaus.

As training age increases, you’ll notice weaknesses that pop up. This information is crucial because it should help guide you into choosing exercises that target your weaknesses. For example, if your back rounds in conventional deadlift having something like front squats in the program will force the upper back to work hard. You may want to emphasis lot of upper back work you be able to keep the torso upright during the pull.

Cons to Conjugate

It can be really hard to see what progress looks like. If there is more weight on the bar than last time you are getting stronger, right? The problem is, some variations place you in such an inefficient position it can reveal a glaring weakness preventing you from expressing how strong your regular barbell lifts are. If you’ve never done a specific variation before it can be an entirely new learning process. Due to the consistently varying movements the body doesn’t really get a chance for skill accusation to occur allowing proper technique to develop. The argument against this that we pick variations that will force proper from to occur. For example, using a box squat with proper form. In my coach experience however, it can take 3-8 weeks of practice with a lift for enough skill development to occur to truly express maximum strength in that variation.

Low recovery cost or more dangerous?

In a way because of the lifters lack of skill they can’t life a lot of weight which can come at very low recovery cost. On the contrary it also can be more dangerous if a lifter is injury prone, isn’t good at adaptability or has low bodily awareness.

If form needs lots of improve, I recommend to keep them doing the regular version of the barbell lift until a baseline level of skill and strength are developed. For most beginners it takes time to master the regular lifts. By changing them on a weekly basis this may cause even more confusion between the lifter and the body. This could possibly lead to lack of interest from the lifter in forms of not able to see progress and never really feeling confident in feeling that they know what they are doing.

The lifter must spend the time to learn how to lift, create the necessary movement patterns for technical mastery and build confidence. I say when a lifter can do that then let the variations begin!

Last words

In the real world there is always a blend of elements the teacher uses to guide the student. There is not one specific way that will work for everyone. There are generalized paths that usually work for most and that’s usually where to start. The paths taken is guided by the student’s skill, adaptability, attention detail, engagement, previous experiences, age, maturity level, willingness and drive. The teacher must encompass all those elements. Through the process the student should learn their own body, limitations (physical and mental), strengths and motivations. The cognate system, done correctly should teach all that. Getting there can be a whole other story.